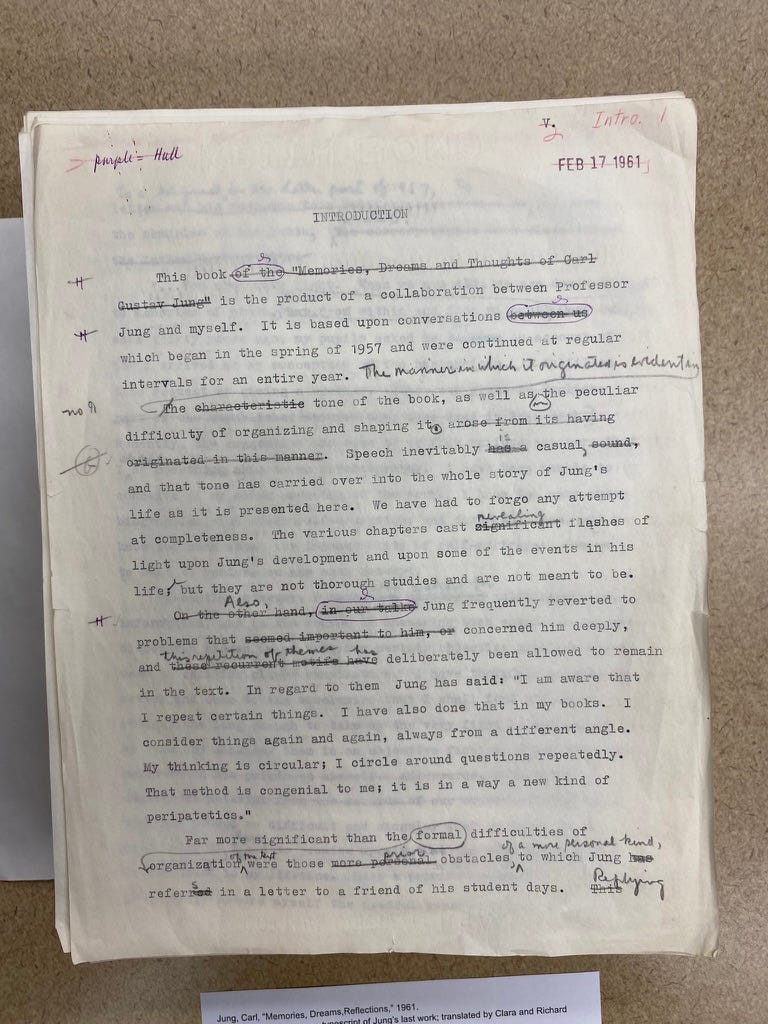

It was a joy to return to Jung’s memoir, Memories, Dreams, Reflections for my recent seminar and then a further delight to be at the Countway Library at Harvard University two weeks later, looking at the original English manuscript, covered in edits from Aniella Jaffe and others.

This expansive work of Jung’s—and the book that introduced me to his psychology in my early twenties—begins with the spiritual and psychological impressions from his childhood, including his now-famous vision of God defiling a Cathedral by pooping on it from the sky. Despite its apparent absurdity, the theological implications of this vision proved prescient for Jung’s unfolding work. The Divine, it seemed to Jung, was fed up with all the Church’s frozen rules. Over time, Jung felt encouraged to follow something more akin to a living God than a set of religious rules that he’d seen petrify so many members of his family.

As Jung came to understand human psychology beyond behaviorism, he identified the core dictate of human nature to be individuation. In essence: follow your own path. Life is a creative act, and rigid precepts—be they religious, cultural, or political—prevent people from living vivid, vibrant lives. Our souls become so tied up in the strings and shackles of right and wrong that we become as frozen as the dogmas themselves. The feminine, Eros, creativity, and the animal-body become alienated and oppressed. Like rivers corralled by cement walls, life can’t find its organic route and people meet their deathbeds feeling restless and unfulfilled.

But, for Jung, defying hardened concepts wasn’t just about freedom. It was also about seeking a new definition of ethics, a new understanding of good and evil, right and wrong. A truly moral life wrestles actively with all of these things and with doubt; it does not allow one to parrot the guidance of others and then pat oneself on the back. He dives into this at length in Memories, Dreams, Reflections (MDR).

“[M]oral evaluation is always founded upon the apparent certitudes of a moral code which pretends to know precisely what is good and what evil. But once we know how uncertain the foundation is, ethical decision becomes a subjective creative act” (Jung, MDR, p. 329-30).

Those who are certain that they are “good” because they are following all the rules are certain only to be casting a long shadow of “bad” somewhere in their lives. A shining example of this was on display in NFL kicker, Harrison Butker’s, shockingly righteous commencement speech last weekend. Amidst all the embarrassing things he declared from his dogmatic perch, the most embarrassing may have been the silent announcement of his psychological immaturity. Having not yet thrown off the inner or outer Father, he was able only to be its mouthpiece. Lacking in psychological creativity, he became a puppet.

No person is yet a psychological adult or can be truly engaged in an ethical life by imitating someone else’s existence, by spending it casting judgment on others, or by living in perpetual shame for the life they hope to live. While not always righteously expressed, living without a genuine sense of inner authority means that one is always seeking approval or celebration from the outside.

“As a rule the individual is so unconscious that he altogether fails to see his own potentialities for decision. Instead he is constantly and anxiously looking around for external rules and regulations which can guide him in his perplexity” (Jung, MDR, p.330).

Some of this is inevitable, and so much of it comes with time and age. But Jung doesn’t place the blame with individuals for a lack of development in this space. He saw it as a culture-wide problem, one that is as true today as it was when he wrote some sixty-five years ago.

“[A] good deal of the blame for this rests with education, which promulgates the old generalizations and says nothing about the secrets of private experience. Every effort is made to teach idealistic beliefs or conduct which people know in their hearts they can never live up to, and such ideals are preached by officials who know that they themselves have never lived up to these high standards and never will” (Jung, ibid).

When we’re confronted with uncertainty and inner opposition, whose resolution is unclear, old rules and common opinion may provide solace and clarity, but not the solution. What then are we to do?

In our private and political lives, we are too often embarrassed by our uncertainty. We have a hunch that something is off, but can’t quite name it. We have a feeling that the people around us are wrong, but can’t quite explain it. We have a sense that what we want is bad, yet we can’t quite let it go and fully question the status quo.

“Nothing can spare us the torment of ethical decision. …[W]e must have the freedom in some circumstances to avoid the known moral good and do what is considered to be evil, if our ethical decision so requires” (Jung, ibid).

Self-knowledge helps. A knowledge of one’s lineage, and of what was left unfinished in our ancestors’ lifetimes. A knowledge too of our fears and longings, and of the guilt that we may carry around and hope to bury in righteous pronouncements about other peoples’ lives.

To participate in the perpetually unfolding creativity of existence, each individual has no choice but to struggle at times with doubt and seemingly irreconcilable opposites. It’s only through this struggle that something new can be born. The transcendent third. The previously unknown middle way. The choice that is not only this nor only that. All known guidance is based on the past and on lives already lived. But we are forever becoming and forever creating.

What else is the point of life?

Related:

Collective Guilt and Our Shadow Selves

I received an unsigned email recently with a request for a specific seminar on “understanding collective guilt.” The writer was curious to know how Jung spoke about catastrophic events and the effect that they have on the individual. I felt an immediate kinship with this mystery writer. I

Really loved what you said here:

"To participate in the perpetually unfolding creativity of existence, each individual has no choice but to struggle at times with doubt and seemingly irreconcilable opposites. It’s only through this struggle that something new can be born. The transcendent third. The previously unknown middle way. The choice that is not only this nor only that."

This is so, so important. More and more, it seems to me that what is most deeply true usually lives in and emerges from the space of paradox. The more we refuse to explore paradox — that two "seemingly irreconcilable opposites" could, somehow, coexist — the more we risk surrendering ourselves to increasingly extreme, zero-sum perspectives.

Such a great essay.

Great piece Satya.

This portion felt synchronous.

As Jung came to understand human psychology beyond behaviorism, he identified the core dictate of human nature to be individuation. In essence: follow your own path. Life is a creative act, and rigid precepts—be they religious, cultural, or political—prevent people from living vivid, vibrant lives. Our souls become so tied up in the strings and shackles of right and wrong that we become as frozen as the dogmas themselves. The feminine, Eros, creativity, and the animal-body become alienated and oppressed. Like rivers corralled by cement walls, life can’t find its organic route and people meet their deathbeds feeling restless and unfulfilled.